OUR PHILOSOPHY AND HISTORY

OUR MISSION & VALUES

Born at the crossroads of Oakville in Napa Valley

The Oakville Grocery mission is to honor our historical roots, build community and offer a carefully curated selection of local, fresh, healthy food and provisions of the highest quality. Born at the crossroads of Oakville in Napa Valley, The Oakville Grocery vision is to inspire a passionate approach to food that is authentic and California at heart.

Integrity

We conduct our business in an open and honest way; our behaviors and the impact of our decisions on a personal, social and environmental level are always considered and at the core of everything we do.

Respect

We embrace our 1881 heritage; it allows us to look backwards and dream forwards as we seek to preserve the legacy and beauty of our land, our historical roots in the community and local food traditions.

Excellence

Our continual pursuit of excellence is the hallmark of our every endeavor; it is simply, a straightforward approach to bringing good food that is local, seasonal and enjoyed by our community and beyond.

Passion

We celebrate the provenance of our food, the people who grow, raise and craft our ingredients. We are passionate about our land and about creating a sustainable, vibrant food community.

Stewardship

We embrace our heritage and long-standing role as a gathering place where great memories and meaningful relationships are made around food and community, now and for generations to come.

OUR HISTORY

Rich in history, dedicated to the future of food

Oakville Grocery has been a wine country institution since 1881. Our flagship location is nestled amongst a landscape of wildflowers and grapevines, rolling hills, and some of the most revered wineries and restaurants in the country, in the heart of Napa Valley. This idyllic locale is now a vibrant gathering place for locals and visitors, wine drinkers and vintners, hungry neighbors and culinary connoisseurs. But that did not happen overnight.

MORE THAN 140 YEARS OF HISTORY

Discover the entire timeline of the Oakville Grocery

1874

Early History

Our story is rooted in hard work and the incredible stories of real people and hard-earned success. Since the first record of our doors opening as P. B. O’Neil’s “dry goods, groceries, and hardware store” in 1874, we have hosted our neighbors through growth, decline, expansion, prohibition, two world wars, and the Judgement of Paris. We have been built, expanded, burnt, restored, and carried forward through history by passionate and innovative owners who were not afraid to open new frontiers. Through changing hands and time, we have always kept our daily intention simple: To be a gathering place where people can eat, drink, share, learn, and grow together.

Today, we proudly operate a value-driven business, promoting California food culture through a highly curated selection of the best products from farmers, artisans, and purveyors in Napa and Sonoma Wine Country. As always, we believe in learning from history as we explore the future, ever pursuing our lifelong mission of creating community through food.

The Oakville Grocery is one of California’s oldest still-operating retail businesses. Its doors were already open when the St. Helena Star ran an ad in its November 19, 1874 edition touting P. B. O’Neil’s “dry goods, groceries, and hardware store” in OakvilleThe store’s name has varied over the years between “Oakville Grocery” and “Oakville Mercantile,” but its location and purpose have been primarily the same.

The Oakville Grocery stood in 1874 where it stands today: near the center of a one-acre square abutting the main north/south county road (now Highway 29) and an east/west road, now the Oakville Crossroad. Immediately to the north of the store in 1874 was a large, elegant, two-story house. It, too, is still there and is now an interactive museum highlighting the history of the Napa Valley and its signature industry: premium wine.

When an Oakland-based publishing company named Smith & Elliott came to the Napa Valley in 1878 to create a book of lithographs describing the local history and architecture, they included a rendering of the building owned by wheat farmer James J. McIntire and his family. “The residence,” Smith & Elliott wrote, “is the finest in that part of the county.”

While wheat's importance as a cash crop was declining in Oakville, the future for grapes and wine looked increasingly promising. Local wine was sold commercially in Napa for the first time in 1857 and was flowing in a steady stream in the Napa Valley by the mid-1860s, especially around St. Helena, which was 6 miles to the north. By the 1870s vintners were on the way to perfecting their craft. Vineyards replaced wheat fields all around Oakville.

Napa Valley enterprises turned over fast in the 1870s, as most people who went into business did so with little prior training and poor financial skills. Then as now, making a profit required a reliable flow of visitors with money to spend as well as the presence of items people wanted. Together, the miners, wheat farmers and wine growers of Oakville lacked the economic mass necessary to support much commerce. There is no evidence that O’Neil possessed suppliers to keep his stock fresh, either: another prerequisite for running a successful retail store.

While Smith & Elliott were writing their history and preparing their lithographs, the Oakville Grocery and the land on which it stood changed hands several times, from John Garner to P.B. O’Neil to a wheat farmer named T. J. Roberts, to a former gold-miner-turned-quicksilver-miner, Jim McQuaid.

1881

James (Jim) and Jennie McQuaid

Jim and his much younger wife Jennie would become the first to make a go of it.

A June 10, 1881 Napa County Reporter advertisement reported on “Oakville Station—Where James McQuaid officiates as Railroad agent, Postmaster, and Wells, Fargo and Company’s agent, also dispensing at a reasonable figure, all kinds of general merchandise to people of the vicinity, from a calico dress to a keg of tenpenny nails.”

McQuaid tended the store and trotted across the county road to the train stop several times a day to assume his role as a railroad agent. As the article showed, he also served as the postmaster, housing the Oakville post office in his store. Pioneer Oakville vintner William Locker was the first Oakville post-master. This essential gathering place for Oakvillans may have been located at the railroad depot during O’Neil’s time but was definitely in McQuaid’s store by 1881. The ad suggests that the McQuaids did not specialize in the sale of groceries, although they were sold at the Oakville Mercantile as they would have been in any general store at the time, especially when there was no other place nearby where residents could buy staples.

The store’s success lured others into trying their hand at retail sales nearby, including a blacksmith and a butcher shop. At least two saloons went into business to “serve the men of the community” and offered wine from the nearby wineries. The transition from wheat farming to grape growing and winemaking was well underway, and times were good.

Things hummed along nicely for the McIntires, the owners of the adjacent farmhouse, and the McQuaids until 1884, when tragedy struck the McIntire family. After a wagon accident claimed his wife and one of their children, a grieving James McIntire sold the store, the house and the one acre they stood on to Jim and Jennie for $700.

Years of mining caught up to Jim, and his health deteriorated. When Jim became too sick to work, a German named Melchior Kemper Sr. bought Oakville Mercantile (its name at the time). Jim McQuaid passed away on August 4, 1889.

1893

The Fire of 1893

Melchior Kemper Sra miller with the Starr Flour Company in Vallejo, most likely first visited Oakville to handle the wheat harvest. Kemper’s teenage son, also Melchior Kemper, clerked in the store, gradually taking many of Jim’s old duties, including operating the telegraph. After the marriage between Mel Sr. and his wife Alice ended, Jennie McIntire married Mel Sr. in 1892 and spent at least part of her time in Vallejo.

Jennie and Mel Sr. enjoyed the company of their prestigious Oakville neighbors. Inspired by affluence, Mel Jr. installed a public telephone in the store: the first of its kind in Oakville. It was expensive, but the novelty could have attracted curious, would-be shoppers.

The night after the Fourth of July, 1893, disaster struck the hamlet of Oakville. Jennie was sleeping in the old Victorian, but the elder Kemper happened to be spending that night on the second floor of the train depot with Mel Jr. According to the Star, he was awakened shortly after midnight by a bright light coming from his store across the road. He roused his son, who had just gone to bed after celebrating the Fourth in St Helena, and the two ran out to find the back room of the store on fire. The blaze spread quickly to the blacksmith shop, a barn and butcher shop, accelerated by the explosion of two cans of powder and 10,000 cartridges the Kempers were storing. Oakville Mercantile, the barn, the blacksmith’s and Walters’ shop all burned down, but the Victorian was spared.

Except for the depot, some saloons and the wineries, the entire commercial center of Oakville vanished that night.

Kemper may have supervised the rebuilding of the store, but at some point, he returned to Vallejo and resumed working at the Starr Flour company until his death in 1909. Shubael Wardner, a merchant who had been living in Pope Valley, took over the store operations. He also served for one year as Oakville Postmaster, starting in 1896. Joseph M. Booth succeeded him in that role in 1897.

1904

Durrant & Booth

The 1900 Census reveals that Booth and his brother Willis were grocers. It also mentions an Englishman named Frederick Durrant as the owner of a “grocery store” in Oakville—not a dry goods store.

The Booth brothers and Fred Durrant had what appears at first a complicated relationship. Fred Durrant, born in 1872, was the stepfather of Joseph Booth (born in 1874) and Willis Booth (born in 1878). Fred had married their mother; a widowed German named Helena, who was 17 years his senior. They had a son together, Fred Durrant Jr.

When Helena Durrant died in 1904, Durrant & Booth were able to complete the purchase of the property and the adjacent house from Jennie and Mel Kemper Sr. Joe Booth and his wife and four children along with the Fred Durrants Sr. and Jr. all moved into the Victorian house and got to work expanding the store.

They built out the 20’ x 14’ area to the width of today’s Oakville Grocery, although not the length. Common for buildings of that time in the Napa Valley, nothing was insulated, nor was there a foundation: Wooden pilings dug into the ground supported the structure.

After the building was completed, it settled into the terrain a bit. The soil may have been softer on the southwest corner because the floor sagged in that direction. A modern-day examination of the wiring suggested that there was no electricity at first. No phonebook lists the store until 1926.

Behind the store on the north side, they built a separate 8’ x 8’ stone cellar for storing perishable meats, cheeses and other items requiring protection from the warmth of the day. A cement slab incised with “1904” lay at the entrance to this partially sunken chamber, and a vent located on the southern wall near the roof allowed heat to escape. It was made even cooler by the placement of blocks of ice packed in cork or sawdust and brought in daily by the train.

1900-1910

Turn of the Century

The first decade of the 1900s was transitional for Oakville, as the fire and a costly phylloxera situation across the vineyards in the previous decade had closed some doors but opened others for those in the wine industry. This evolution meant more shoppers at the store, and Durrant & Booth were happy to procure hard-to-get items for their new, upper-class neighbors.

Infrastructure features like churches and schools would be essential if Oakville were to grow into an actual incorporated town. There were some indications that this was on peoples’ minds because when all the debris from the fire had been cleared away, other buildings went up on and around the one-acre square. A new store on the corner of the county road and the Oakville Cross Road replaced the old butcher shop. It was a saloon with lodgings of some kind on the second floor. An upgraded blacksmith shop between the new pub and the grocery/mercantile store weened itself from horses and offered autos for hire. Above it was a meeting place, Oakville Hall, that served as a combination town hall and gathering place for community events, like dances.

Cars gradually replaced the horses and buggies of the past. Real estate magnates, business tycoons, and wealthy families flocked to the area. Everyone in Oakville, rich and poor, now shopped for necessities at Durrant & Booth. They came by horse, on bicycles, in cars, and on foot.

Patrons bought 200-pounds of flour at a time and sugar in 100-pound sacks. The store sold chicken feed and salt licks, clothing, ammunition, shoes and many other things useful to rural families. Eggs, dairy products, and some produce were available, as well as a lot of candy, medicines and local wines by the bottle.

1911

Growth and Temperance

With the Booth brothers clerking in Oakville, Fred Durrant moved to San Francisco and opened a grocery store at 1290 11th Avenue, in the Sunset District. This area was just being converted from an “outside lands” of sand dunes to a residential district. Having a city store and a country store created a steady flow of new supplies: something that had eluded the OG’s earliest owners. He sold Napa Valley wines in his San Francisco store, as well as country-raised items like fresh milk, fresh butter, and fresh eggs, while he sent trendy apparel and hard-to-find hunting equipment to the Oakville store.

When Joseph Booth left the OG in 1911 to take a job at the Naval base at Mare Island, Fred returned to Oakville and did a brief stint as grocer/postmaster again. He found new partners for Oakville, Benjamin Hooks (a former mining superintendent whose father had run a small Oakville winery) and Arthur V. James. This arrangement seemed to work well and continued for another six years. Hooks and James handled the mail and dealt with the store while Fred returned to his business in San Francisco to sell wine and other Napa Valley items. The supply chain was preserved, and the store experienced a period of stability, at least for a few years.

Life in America in the 1910s was difficult for a large portion of the populace. Health care was inadequate, money often hard to come by, and there were few safety nets to prevent the afflicted from falling into severe poverty. Women continued to be especially vulnerable to penury, particularly women with children. Increasingly, the finger of blame for many of life’s evils was pointed at the consumption of alcohol.

The Women’s Suffrage movement and the Temperance movement proceeded hand in hand, each empowering the other. In most households, men brought home the paychecks and subsequently spent time and money in saloons. Women drank, too, but rarely in public. Women often fell victim to addiction to the opiates regularly peddled as cures for various ailments. Old bottles recently discovered hidden beneath the floorboards of the Oakville Grocery originally contained cure-alls with high alcohol content and may have included more harmful ingredients, as well.

1917

Prohibition and the Great Depression

In 1917, to prepare for America’s entrance into the impending war in Europe, President Wilson signed into law the mandatory closure of saloons and other establishments selling alcohol within a five-mile radius of any military installation. Oakville was within five miles of the Veterans Home in Yountville, which was technically a military installation. This proximity meant that all of Oakville’s vintners and saloon-keepers had to close down their businesses. Wilson’s order added fuel to the Prohibition movement, which became the law in 1920, although Oakville felt its effects well before.

Since Napa Valley wines had been a significant part of the inventory in his store, Fred Durrant was now out of business in San Francisco and returned to the Oakville store in 1921.

Then something unexpected happened. Tourists from the Bay Area started driving to the Napa Valley for an extraordinary treat: bootlegged wine and liquor. It was so well known that fermented products could still be obtained in the Napa Valley that the American Legion made a float, “The SS Bootlegger,” with a sign declaring it a rum-runner from St. Helena, “where the good grapes grow.” Alcoholic beverages were available by the jug or the glass if you knew where to look. More than 2,000,000 motorists crossed the newly constructed Carquinez Bridge one year during Prohibition, many of them driving up the county road and past Durrant’s store.

Selling prohibited products to tourists on the way to St. Helena would have been both risky and unnecessary for Durrant, whose honest disposition would have prevented him from breaking the law, even if he disagreed with it. The store instead was well-positioned to supply sandwiches, sunglasses, hats, maps and other non-alcoholic provisions to out-of-town visitors. The promise of Coca-Cola would have been an especially potent lure for travelers.

Travelers could stock up on fresh eggs, dairy products, and farm-grown fruits and vegetables on their trip back to the Bay Area. With access to gardens like Doak’s, Churchill’s and others, Durrant’s wares were fresher than anything in San Francisco. Happy to target the tourist trade with temptations like ice cream, Durrant borrowed money to make upgrades at the store. He added refrigeration units and deepened the store’s footprint. The store became a beacon in an otherwise bleak landscape, at least from a commercial point of view.

Durrant’s store remained a local mainstay through Prohibition and the following Great Depression due to its diversification and focus on non-alcholic goods. Most vintners who attempted to reopen wineries after Prohibition ended in 1933 were met with too many problems to continue. Of the 145 wineries in operation in 1918, only a few were legally active in 1933.

Prohibition and the Great Depression had all but ended the market for premium California wine. Vineyards gave way to orchards of walnut and prune. Durrant’s Oakville store served as a local mainstay to the 1970s, when Durrant sold the store to John and Pam Michel.

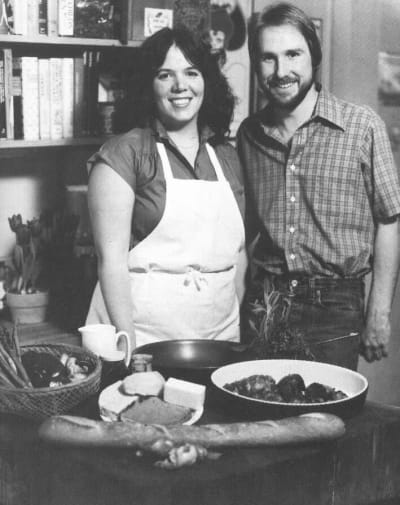

1970's

Growth and Luxury

To test whether there really was a market for high-end culinary products in rural Oakville, the Michels displayed 75 different varieties of mustard. When those flew off the shelves, they added artisan cheeses, fresh herbs, spices, an array of mineral waters, a selection of caviars and other items that had never seen their way into a store in the Napa Valley, let alone Oakville.

While the items for sale at the Grocery evolved from the ordinary to the extraordinary, the Michels were careful not to alter the history and feel of the old building. The old glass-paned candy case remained. People could still charge to their house account, and the post office continued to serve as a local meeting place. Several upgrades were necessary, however, to display their wares correctly. These all came over time, as money started to trickle in. They built an island in the center of the building for preparing sandwiches and added a new cash register. A juicer provided tangy refreshment by the glass. They converted the 8” x 8” stone cellar into a wine shop featuring vintages from small local wineries and selected imports.

The Michels installed a feature few people had experienced: a coffee bar with brewed coffee made from fresh beans, rather than percolated from cans of pre-ground. Pam made salads and other items for take-out lunches, as it was done in New York. She and John grew some of the produce they sold and displayed it in welcoming straw baskets.

John sought out purveyors of obscure ethnic food in San Francisco and located new suppliers for more unusual condiments. Cornichons, olives, yogurts, cheeses and rare herbs and spices found their way into his inventory, much to shoppers’ delight. The best Italian olive oil, imported dried pasta, and artisan vinegar now lined the shelves and filled the baskets, inviting patrons to expand their tastes. Fresh produce and freshly-baked bread were essential to the business. John found a supplier of baguettes, Passini, which was a novelty in 1974. Where the old store used to carry hot dogs and packages of Hormel cold cuts, the Michels displayed patés and goat cheeses, as well as imported, cured meats usually found only in major metropolitan centers.

The Oakville Grocery was situated very close to the road, and parking was an issue. The owner of the Oak Rail bar and grill rejected their pleas to let patrons use their parking lot. Concerned about the safety of their patrons—and worried that the parking problem might discourage would-be shoppers—John and Pam offered, in 1975, to rent the Oak Rail using the money they borrowed from family members. The owner agreed.

They moved the coffee bar and its associated baked goods to that space and served light lunches and alcoholic beverages at the grill. John began the morning at the Grocery and spent most of his day re-supplying inventory. Pam took over after school let out, while John tended bar at the Oak Rail. At night, Pam cooked for the store as she did her school lesson plans for the next day and prepped for the cooking class she taught at Silver Oak Winery just down the road. Despite hiring a co-manager, Pam and John did not get much sleep. Then two propitious events in 1976 combined to send torrents of customers their way.

That May, at the respected “Judgment of Paris” blind tasting in France, local Napa Valley wineries did unexpectedly well. This encouraged wine enthusiasts who had written off the Valley years before to come back for a second look. The Paris success dovetailed with a project that Margit Mondavi spearheaded: the Great Chefs program at Mondavi.

Now that the Oakville Grocery had made it possible for Napa Valley residents to buy hard-to-find ingredients, Mondavi realized she could ride the new wave and further the area’s sensory education. She invited some of the world’s most renowned chefs to teach cooking classes at the winery. For a significant fee, food lovers could learn nouvelle cuisine and cuisine classique from a lineup of phenomenally gifted chefs. She established a series of exclusive five-day courses taught by masters of French cuisine as well as American culinary leaders like Julia Child, Wolfgang Puck, Alice Waters, Jeremiah Tower, Jan Birnbaum, and Thomas Keller.

The Mondavi winery’s in-house culinary team managed the Great Chefs program. They prepped the ingredients, ran the kitchen staff and provided John and Pam with the recipes well in advance so they could stock the shop with the necessary ingredients. People came from all over the Bay Area, and eventually from across the globe.

1970's

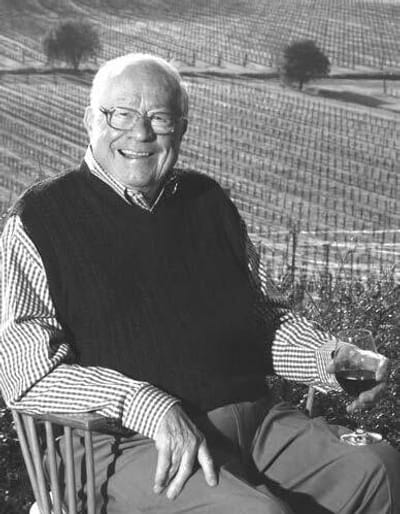

Joseph Phelps and Steve Carlin

Successful but overworked, the Michels were relieved when Joseph Phelps, a prominent Napa Valley vintner, saw an investment opportunity in their store. Phelps was relatively new to the Napa Valley. He had been running a construction company in Colorado and had no prior experience in the wine industry when he won the bid to build Souverain Winery (now Rutherford Hill) in the 1970s.

Recognizing the untapped potential in the wine industry, he bought a cattle ranch off the Silverado Trail in St. Helena. In 1973—the same year the Michels bought the Oakville Mercantile—Joseph built a winery of his own. He had developed a keen appreciation for fine foods and was himself an excellent cook and had come to treasure the Oakville Grocery. When he heard from Jean Michels, John’s mother, that business was booming at the Oakville Grocery, but the workload was crushing her son and his family, Joe offered to buy out John and Pam while retaining John as an employee. They jumped at the chance.

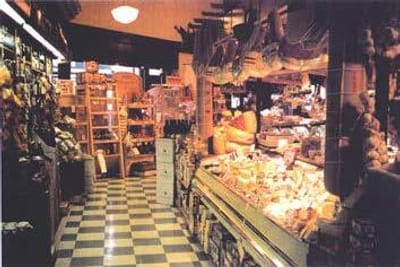

To keep abreast of changes in the field, John traveled back to New York and met with the founders of Dean & Deluca, Joel Dean and Giorgio DeLuca. They had opened their “corner grocery store” in SoHo in 1977, offering guests artisanal gourmet specialties similar to those in Oakville. The original Dean & DeLuca was reminiscent of a turn-of-the-century emporium, with spinning fans dangling from the very high ceiling and colorful, lavishly overflowing displays. Their shelving, however, was avant-garde: shiny, chrome-colored “metro wire” that collected no dust and gave the store a feeling of modernity and airy freshness. He also learned of their plans to expand to a much larger and posher store and to branch out to other cities.

When he returned to California, John convinced Joe not only to tear out the shelving and install metro wire (John and Pam did the work themselves); he also went to San Francisco to scout locations for a new Oakville Grocery there. He found a two-story building at 1555 Pacific Street between Polk and Larkin, and Joe leased it.

In terms of foot traffic, the Pacific Street location was tolerable. (It was in a mixed-use area of homes and small businesses.) As it had been in Oakville, however, parking was an issue. John hired valets to help with it. He chose to manage the store himself, and he selected an enterprising former musician, Steve Carlin, to run the Oakville business in his absence.

The Pacific Street location boasted even more prolific offerings than its Oakville sibling, with more than 100 cheeses, fresh pastries and an expanded selection of mustards and condiments. The charcuterie program was more evolved, with imported cold cuts, fresh sausages, and prime meats, poultry and fish. It attracted the attention of food writers and epicures from near and far. An artist friend of John’s developed a logo: the profile of a “fierce bunny.”

Food critics wrote lovingly of the San Francisco store. A columnist from the Dallas Tribune extolled its unique inventory in a way that may have left readers wondering if it was a grocery store at all. Despite these rave reviews, the store quickly ran into serious roadblocks. In addition to the parking dilemma, labor issues arose. Most of the employees were young, enthusiastic and eager to please. However, the store was not unionized, the staff received minimum wage, and all the publicity it had received drew the attention of the Teamsters Union. Picketers came, discouraging patronage. The store lasted less than a year. Joseph Phelps and John Michels parted ways, John moving on to develop some prestigious food departments in high-profile settings, among them The Cellar at Macy’s.

Meanwhile, up in Oakville, Steve Carlin was proving to have not only a superb palate but good management skills, as well. Joe Phelps and silent partner Tom May financed another round of enhancements, giving the wine program a new home that occupied the entire back section of the store.

1981

The Culinary Boom

As the national economy emerged from the malaise of the 1970s, interest rates fell, and money became more fluid. The idea of escaping modern times and finding a quieter pace of life was appealing, especially to those who could afford to invest in vineyards and wineries. More than 100 new wineries sprouted in the Napa Valley in the 1980s, very much as they had in the years around 1881. Tourism rose throughout the ’80s as more and more visitors discovered treasures in the Napa Valley. The general population was also enjoying an increased appreciation for fine food and drink, thanks to the Oakville Grocery and similar places that were opening elsewhere in the country.

Having before regarded the Napa Valley as too remote, a few first-class restaurateurs were privy to the natural genius of pairing the wine experience with excellent food. Claude Rouas opened Auberge du Soleil in Rutherford in1981, followed by Piatti in Yountville. Soon many other top-rated chefs followed, like Cindy Pawlcyn (Mustards Grill, 1983) and Michael Chiarello (Tra Vigne, 1986). The mutually enhancing and beneficial relationship between good wine and good food sponsored a period of great awakening in the Valley, both economically and culturally. Mercedes Benzes, B.M.W.s, and chauffeured limousines filled the parking lot at Oakville Grocery, and the store prospered like never before.

Oakville was again being recognized as the best of the best, and the staff at the Oakville Grocery was exceedingly knowledgeable. A former employee, Christie Shelley, worked there in her teens after school and on weekends. She recalls:

All the employees were like professors of food. They knew their cheeses, wines and deli goods. I stayed out of the way stocking shelves and sweeping the floor...There was no air conditioning. On summer days in the valley, things heated up. I remember sitting on a milk crate in the large cooler, stocking sodas and making sure the new drinks were in the back and the colder ones up front. One of the food professors walked in holding a paper bag, asking me if I wanted to smell the most amazing thing ever. He was sniffing the inside of this brown bag and practically doing somersaults. Whatever was in there was magical in his mind. I had no idea what it was at first, but it indeed was the most fantastic scent I’d ever experienced in my life. Earthy, musty, sweet and salty all at the same time – truffles imported from France... They were practically out the door as soon as they arrived...

In 1992 the stock market took off, increasing the amount of wealth available for discretionary purchases like high-end wine and fine foods. It also provided funds for research and development in other burgeoning industries, particularly technology. Some who saw fast successes came to Napa Valley with their fortunes.

1994

The Expansion

Joseph Phelps and Steve Carlin believed the time was right to open other Oakville Grocery stores. They tried to avoid one of the more severe problems John Michels had encountered by finding locations with ample parking. They chose Palo Alto and marketed their offerings to a younger, more urban crowd than those who typically shopped in Oakville. About six times larger than the Oakville facility, the Palo Alto outpost offered prepared meals like skewered chicken, grilled shrimp, Pad Thai, and salads composed of hard-to-find, exotic ingredientsWell-trained deli staff with state-of-the-art equipment cut imported prosciutto, bundnerfleisch and finnochiona into slices fine enough to suit the pickiest gourmet, and patrons could eat their purchases at tables on the nearby patio.

The next store opened in 1994 in downtown Walnut Creek, drawing in foodies with a taste for culinary specialties like arancini and soppressata, as well as the expected array of imported chocolates, fine cheeses, homemade soups and obscure condiments. Dinner selections like hot roast beef, leg of lamb Provençal and crispy duck were available to order via the store’s website for pick-up or home delivery.

Encouraged, Phelps and Carlin pulled out all the stops and built a grand Oakville Grocery (5,600 sq ft) in Old Town, Los Gatos. There they launched more than a dozen Oakville Grocery-branded items, including infused oils and vinegar, condiments, herbs, spices, and even wines, as well as slippers and robes, and they published a mail-order catalog to facilitate purchases.

In 1997, they opened another branch in Healdsburg, a rural-feeling village of fewer than 12,000 people on the Russian River in Sonoma County. The Oakville Grocery there was well placed on the southeast corner of the historic Central Plaza. Patrons dined on lovingly crafted sandwiches, specialty salads, and other lunch offerings at picnic tables beneath the welcome shade of umbrellas. Here, too, a very generous wine selection was available, including those from the nearby DeLoach Vineyards. The first chef at the Healdsburg store, Jeff Mall, had worked at Jeremiah Towers’ Stars Oakville Café and had a good feel for the kind of operation that would reflect the historic ambiance there, remaining true to the original concept of serving excellent food in a relevant setting.

The flagship store in Oakville, meanwhile, continued to thrive. More than 80% of the Grocery’s guests drove there from out of the Valley. Parking continued to be difficult, especially with the increasing popularity of long limousines, so the Phelps family worked out an agreement with Opus One to swap some land. They demolished the housing units behind the store and installed a driveway with parking spaces that surrounded both the Victorian house and the store.

2002

Woodside Capital Partners

From a sales perspective, the expansion campaign seemed to be working, but from an overhead standpoint, the numbers were less enchanting. While people were willing to spend top dollar for a hand-folded Mezzaluna or hand-crafted Buffalo Mozzarella, landlords were now ready to charge top dollar for renting space. As Safeway and other mass-market retailers began to stock premium products, the law of diminishing returns was apparent. To protect the bottom line, the Walnut Creek and Los Gatos outposts both closed in 2002.

In 2003, Joe Phelps released his control of the Oakville Grocery Company to Woodside Capital Partners, an investment company, although he kept a financial interest in the Oakville Grocery and retained ownership of the land. Carlin left to help develop the Ferry Building Marketplace in San Francisco and then the Oxbow Public Market in Napa, of which he became the majority owner.

Woodside Capital inflated the Oakville Grocery even further, veering away from the original rural store concept.

The American economy, in the meantime, was putting on the brakes, hard. The original Oakville Grocery was doing fine, but suddenly Woodside Capital, now its parent company, was not.

2007

Leslie Rudd: Renovation

In 2007, just as the economy was approaching its darkest hour, an entrepreneur and fine food enthusiast fortuitously stepped in to help the ailing business. Leslie Rudd loaned Woodside the cash to cover immediate expenses and took over ownership of the Oakville Grocery. He closed the Palo Alto store and decreased the stock of imported items at Healdsburg and Oakville.

Leslie Rudd had a sensitive, refined palate and an epicure’s appreciation for food and wine. As his successes in real estate and liquor distribution mounted, he was able to invest in ventures that spoke to his passions. Rudd made a special purchase in 1996: the Dean & DeLuca chain of fine food stores that had so impressed John Michels. He opened outposts of Dean & DeLuca in Charlotte, Kansas City, Tokyo, Taiwan, and St. Helena before selling the chain to a Thai company in 2014.

Rudd loved history. Over the years he had bought and restored quite a few historic buildings around the country. Authentically old, the Oakville Grocery exuded history, even if the wares seemed ultra modern. By 2011, it was all too apparent that the building in its present physical condition had reached the end of its lifespan. Without a solid foundation, proper insulation, and modern plumbing and electricity, the store could not continue to thrive. The building’s sag to the southwest was ever more pronounced, and the wall studs seemed held together by the shelves they supported. As one carpenter quipped, all that kept it standing was a habit.

To Rudd, tearing the old thing down was out of the question. It was on the National Register of Historic Places, but even if it hadn’t been, its intrinsic beauty and the history it had seen made it worth saving. Rudd hired Guy Byrne, a contractor sensitive to the painstaking and delicate task of retaining all the salvageable elements. Crews began to dismantle the structure in January 2012 and completed it in May of that year. The Victorian house—renamed the Durrant & Booth house—was also restored and converted into a setting for administrative uses.

Leslie Rudd passed away in 2018, and Jean-Charles Boisset bought the Oakville Grocery and the Durrant & Booth house.

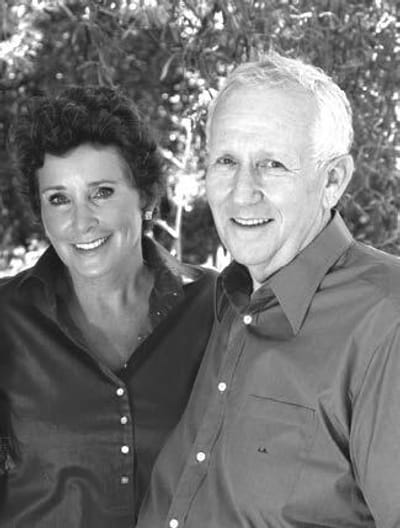

2018

The Present

Jean-Charles Boisset (JCB) was born in 1969 in Vougeot, France, an ancient and iconic viticultural area in the Burgundy region. His father is a vintner, and the family owns historically significant vineyards and wineries throughout France, from the mountainous Jura region to the Rhone Valley and Beaujolais to Languedoc in the south. With such antiquity all around him, it is little wonder that JCB grew up with a passion for history.

JCB’s approach to viticulture and winemaking is both modern and quite ancient. With great respect for terroir and the natural vinification process, the farms and makes wine organically and Biodynamically. He values the reciprocal relationship between the land and what it produces and knows that for a planet in peril, the principles of locale, purity, and sustainability must be the model that drives the future of agriculture. He finds much satisfaction in rehabilitating worthy old vineyards by applying natural remedies that restore health to the vines while safeguarding the ecosystem. As in the case of the Oakville Grocery, worthy old buildings are also the recipients of his love for restoration.

I discovered the Oakville Grocery when I was 11 ½ and touring California with my grandparents and my sister. A lover of history even then, I marveled at the rustic feeling of the place, which spoke to me of the courageous American pioneers I had read about in my native France.

My warm regard for the Napa Valley and neighboring Sonoma has remained with me ever since, and when the opportunity arose to acquire the store and adjacent Victorian house, I was eager to add them to my family’s collection.

—Jean Charles Boisset.

It is this appreciation for the authentic, the historical, and the relevant that prompted JCB to take over what Leslie Rudd had begun, but he is guiding it in a new direction. Boisset’s version of the Oakville Grocery, unveiled in 2019, specializes in food that is locally grown, carefully curated, artistically displayed and free of pesticides or synthetic fertilizers. Food is not selected for its exotic qualities, as it was in the 1970s Oakville Grocery, or for its convenience, like in the 1950s, but for its purity, quality, sustainability, and locale.

Jean-Charles has transformed the adjacent Durrant & Booth house, with its magnificent view of the mountains to the east and west, into a tasting lounge and wine merchant specializing in both core and cult-worthy wines from the 16 sub-regions within the Napa Valley appellation. Both the house and the store draw attention to the year 1881 when the Oakville Grocery’s roots first really took hold as a mainstay in the heart of the Napa Valley.

The Oakville Grocery has welcomed people across its threshold for at least 135 years. The little roadside business has somehow managed to survive revolutions in transportation, upheavals in the economy and the exodus of almost all of Oakville’s population. With one foot in the present and one in the past, the history of this humble but resilient store reflects the story of the Napa Valley itself.

BOISSET FAMILY

Jean-Charles Boisset, aka JCB, leads Boisset Family Estates, a wine company founded in France in 1961 by his parents, Jean-Claude and Claudine Boisset.

The Boisset family now owns historic wineries and vineyards in France, Canada and England as well as in Monterey (Lockwood Vineyard), Sonoma County (Buena Vista Winery, DeLoach Vineyards, Lyeth Estate and Wattle Creek) and in Napa County (Raymond Vineyards).

In addition to the Oakville Groceries in Oakville and Healdsburg, which focus exclusively on locally grown foods, the Boisset family offers a very European choice of charcuterie at their Atelier Fine Foods and Catering, headquartered in Yountville. Atelier also features some special local offerings like honey from beehives at their wineries and olive oil from the Napa Valley.

Get to know Our

ARTISANS & PURVEYORS

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

Nunc dictum lacinia lectus, non gravida libero.

Discover MORE